The first empresario colonies formed in the land that became Texas were created under Mexican rule, and four were created during the Republic of Texas era.

In the Republic of Texas a land grant system was devised to designate "colonies" and bring immigrants to the Texas frontier. The original plan was that Contractors, called Empresarios, were to receive 10 sections of land for each 100 colonists introduced and up to half of the colonists' grants. Colonists were to receive grants similar in amount and requirements to fourth class headrights (a status issued to those who arrived to Texas between January 1, 1840 and January 1, 1842 - see info on Headrights, below), with the requirement of each land owner placing 15 acres into cultivation.

Under the Republic's land grant system four contracts were made to designate colonies and bring immigrants to the Texas frontier. However, those contracts varied, and the laws dictating land amounts were not adhered to. Those four Republic of Texas colonies were Peters' Colony, Fisher - Miller's Colony, Castro's Colony and Mercer's Colony.

A North Texas empresario grant made in 1841 between the Republic of Texas and twenty American and English investors led by William S. Peters, an English musician and businessman who immigrated to the United States in 1827 and resided in Pennsylvania. Half of the investors were residents of England and his sons and sons-in-law, and the other half were residents of the United States. This colony was plagued by squatters, disgruntled directors and colonists, changing laws and litigation instigated by both colonists, politicians and land brokers who named their venture the Texas Emigration and Land Company. However, the troubles between colonists and the company did not end until the late 1870's.

A land grant was originally issued on 7 Jun 1842 to Henri Francis Fisher, Buchard Miller and Joseph Baker, comprising some 3,000,000 acres of land between the Llano and Colorado Rivers, the grant became known as the Fisher - Miller Colony. The three would-be empresarios proposed to settle 1,000 German, Dutch, Swiss, Danish, Swedish and Norwegian families on the huge tract by March 1, 1845. However, travel from Europe at the time took months, even years, and although colonization was started and the first settlement of New Braunfels was started in 1845, the first certificate was not legally issued until 11 Aug 1851. After many problems the land company was taken over by the Society for the Protection of German Immigrants, and later the German Immigration Company, because of the great inhumanities of disease, Indian depravations and starvation suffered by the first immigrants brought to Texas.

On February 15, 1842, Henri Castro received contracts for two grants of land south and west of San Antonio, on which he was to establish 600 families in an Alsatian colony of French immigrants. The colony suffered from Indian depredations, cholera, and the drought of 1848, but survived to create several counties and present day towns of Castroville, D'Hanis, Quihi, and Vandenburg.

Charles Fenton Mercer, a member of the House of Representatives from Virginia, secured a colony as a land grant from the Republic of Texas in 1844. Mercer's colonizing association was officially called the "Texas Association" but is more commonly referred to as Mercer's Colony. The colony grew out of a statute enacted by the Texas Congress on February 4, 1841, restoring the Mexican policy of granting empresario contracts to persons who promised to survey the lands and settle individuals and families on the unclaimed public land of the republic.

Republic of Texas President Sam Houston granted Mercer a contract to settle at least 100 families a year for five years, beginning on January 29, 1844, despite opposition from Texas' current residents. Mercer soon organized the Texas Association, to advertise and promote colonization, and sold shares at $500 each to investors in Virginia, Florida and Texas.

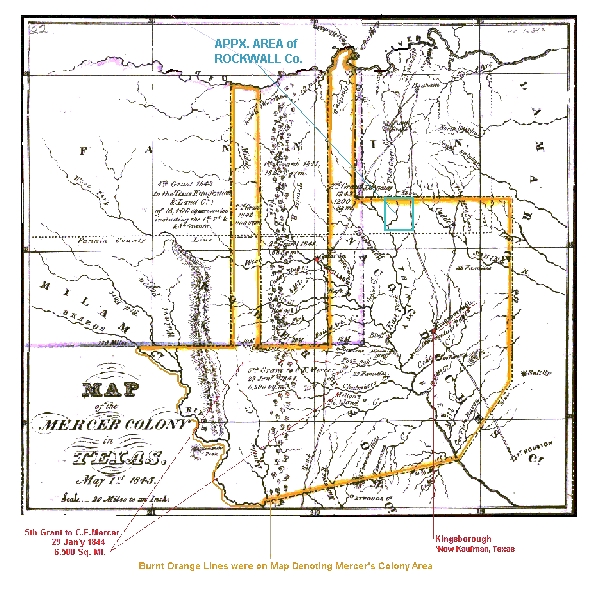

The colony was located east and south of the Peters colony, and lay between the Brazos and Sabine rivers, north from Waco to McKinney in Collin County, covering all or part of 18 present Texas counties, including Hunt, Rains, Rockwall, Kaufman, Van Zandt, Henderson, Navarro, Hill, McLennan, Johnston, Ellis and Dallas.

The colony initially offered only 160 acres to families and eighty acres to single men, but because the Peters Colony promoters were offering 320 acres, and later 640 acres to men and women with families, the better offer drew perspective colonists to that colony before Mercer finally matched the offer. Nevertheless, by the end of the first year of the contract, more than 100 families had complied with the requirements and received land certificates from Charles Mercer.

However, the work of colonization was soon impeded by the fact that various land speculators, squatters and politicians, including David Spangler Kaufman, the man for whom Kaufman County is named. They were eager to replace the empresario system with the Anglo-American land system, saying the emprsario system questioned both the wisdom and the legality of granting away the republic's vast public lands without financial gain to the Republic.

To make matters worse, Mercer himself was unpopular with the Republic's citizens for he was known as an abolitionist at a time when slavery was being defended in Texas and had been an issue during the Texas Revolution. He also had the reputation of being an unscrupulous speculator, a monopolist, and an opponent of free immigration for Anglo-Americans. One day after the execution of Mercer's contract the Congress of the republic passed, over President Houston's veto, a statute outlawing colonization contracts. Congressional resentment culminated in an investigation during 1844-45 of Mercer's contract and his efforts to fulfill its terms. Meanwhile, squatters moved into the Mercer survey and denied the claims of settlers who held Mercer colony certificates. Mercer's colonists also discovered land speculators and holders of bounty and headright certificates already claimed the lands for which they had been contracted, many arriving to their new land to find it occupied and under cultivation. At this same time Mercer's surveyors reported that Robertson County, joining the colony on the south, was sending its surveyors into the limits of the empresario grant, claiming the land they surveyed there. Finally, Mercer surveyors and settlers clashed with both civil and military forces when they attempted to penetrate that portion of the grant lying west of the Trinity River. This situation started many years of litigation in the Texas Courts, especially with some of Kaufman County's earliest pioneers.

After the Convention of 1845 instructed the new state of Texas to begin legal proceedings against all colony contracts, Governor Albert C. Horton instituted suit on October 11, 1846, against Mercer and the Texas Association in the district court of Navarro County. Judge Robert E. B. Baylor of the Third Judicial District declared the contract between Mercer and Houston null and void, but the Texas Supreme Court subsequently upheld the legality of the contract. On February 2, 1850, the Texas legislature, seeking to quiet the confusion within the colony, guaranteed all land claims made by settlers in the Mercer colony before October 25, 1848. By virtue of this legislation, 1,255 land certificates were recorded in the General Land Office. In the face of these developments, and in hope of protecting the investments of his associates in his Texas project, Mercer severed all connection with the grant on February 27, 1852, by assigning his interest in the Texas Association to George Hancock of Louisville, Kentucky.

Although settlers recruited by Mercer and the Texas Association were ultimately granted the lands they had settled on, the state of Texas steadfastly refused to legalize any claims of the association itself. Litigation over the lands continued into the 20th century. The commissioner of the General Land Office would not allow The Association to sue in state courts and defended adamantly against all claims that it brought, making available for sale the public lands within the Mercer grant. On March 6, 1875, the chief agent of Mercer's Association filed an injunction in the United States circuit court at Austin, demanding that the land titles sought by the colonists be legalized whether within the area of the Mercer colony grant . The United States Supreme Court settled the issue in 1883 by denying all compensation owed the association that was based on the original empresario contract. However, the ruling failed to halt all conflicting land claims, some of which were in process of litigation as late as 1936.

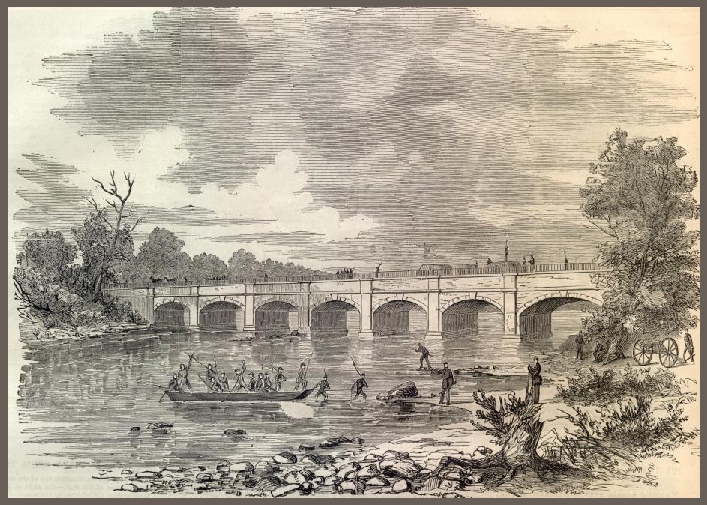

Charles Fenton Mercer, Virginia statesman and Texas empresario, was the son of James and Eleanor Dick Mercer, born in Fredericksburg, Virginia, on June 16, 1778. Princeton College (now Princeton University) awarded him a baccalaureate degree in 1797 and a master's degree in 1800. He was offered commissions as lieutenant and captain of cavalry, United States Army, in 1798 and 1800 but declined in order to study law with George Washington's nephew, Bushrod Washington, a justice of the United State Supreme Court. Mercer was admitted to the bar in 1802 and entered the practice of law in a town he founded with thirty acres of his land - Aldie, Virginia. Mercer began a distinguished career in public service in 1810 with his election to the Virginia House of Delegates, where he served until 1817. During the War of 1812 he held commissions as major in command at Norfolk, Virginia, lieutenant colonel of the Fifth Virginia Regiment, inspector general of Virginia militia, aide-de-camp to the governor of Virginia, and brigadier general in command of the Second Virginia Brigade. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1816 as a Democrat and served in that office from March 4, 1817, until his resignation on December 26, 1839. Charles Fenton Mercer was a man of vision and had futuristic entreprenual ideas. He spearheaded the construction of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, a unique waterway in that it has a stone bridge that allows the canal to travel over the Monocacy River. Water transport over water transport. In 1823, he led a canal convention that included investors like Francis Scott Key. Five years later, he watched President John Quincy Adams break ground for the canal at Little Falls on July 4, 1828. Although John Eaton became president of the canal company in 1833, Mercer continued to serve as an advocate of federally funded internal improvements, such as the canal, while serving in the U.S. House of Representatives.

*An Interesting Notation:

In his public life Mercer zealously pursued three principal interests: development of the American West through internal improvements, promotion of public education through schools established at public expense, and colonization of "free people of color" through emigration from Africa. He was a staunch abolitionist and sponsored legislation in the Virginia Assembly in 1812-13 to establish a fund for internal improvements and to organize and serve as first president of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company, 1828-33. In 1815-16, as a Virginia assemblyman, Mercer unsuccessfully sponsored legislation to establish a system of primary schools. He consistently supported Thomas Jefferson's plan for a University of Virginia. Throughout his career in the Congress of the United States and the Virginia Assembly, he supported bills promoting general education. Long an advocate of plans for the removal of free blacks to Liberia or elsewhere outside the United States, he became active in 1817 in the organization of the American Society for the Colonization of the Free People of Color of the United States. For the next twenty years he devoted much of his time and resources to this and other African colonization projects. In 1839, at age sixty, Mercer regretfully resigned his seat in Congress and accepted appointment as cashier for the Union Bank of Florida at Tallahassee. He offered as his reason for this step the heavy drain on his finances brought about by his long career in public service and philanthropy. While employed at the bank, he became interested in Texas colonization. Then, in 1841, on one of his seven trips to Texas, he began exploring the possibility of bringing Anglo-American settlers to the new republic. Initially his interest was drawn to the Peters Colony in northern Texas, and he traveled to Texas in 1843 as an agent of that colony. Ultimately, however, on January 29, 1844, he received an empresario contract from President Sam Houston for a colony located east of the Peters Colony. Eager to fulfill the terms of the contract, Mercer returned to the United States in February 1844 to obtain assistance in financing and promoting his venture. He soon organized the Texas Association and began selling shares for $500 each. By the end of the year, as a result of his energetic advertising, more than 100 families had complied with the requirements of his contract and received land certificates. Mercer's contract was a source of controversy, however. Houston had granted it after vetoing a bill by the Texas Congress that would have taken away the president's authority to make such contracts without consulting the Congress. Congress overrode Houston's veto the day after the Mercer contract was granted. Mercer's well-known abolitionist sentiments made the colony an issue in the abolition and annexation controversy. Land disputes and the resulting court cases were an additional drain on Mercer's time and finances. In 1852 he assigned his interest in the contract to George Hancock of Kentucky and other members of the Texas Association, receiving in return an annuity of $2,000. He spent the remaining six years of his life traveling in Europe. Shortly before his death he returned to his native Virginia, where he died at Howard, near Alexandria, on May 4, 1858. He was buried in Union Cemetery, Leesburg, Virginia. He never married.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: |